UNREALIZED SCENIC DESIGN for

MIMI LIEN’S SET DESIGN II at NYU TISCH

ALICE IN WONDERLAND

COMPOSED BY UNSUK CHIN

LIBRETTO BY DAVID HENRY-HWANG

THROUGH THE LENS OF THEATRICALITY, AN INSTRUMENTALIZATION OF THE FAMOUS FABLE TO TELL THE STORY OF A VIOLENT IMPERIAL POWER IN DECLINE

.

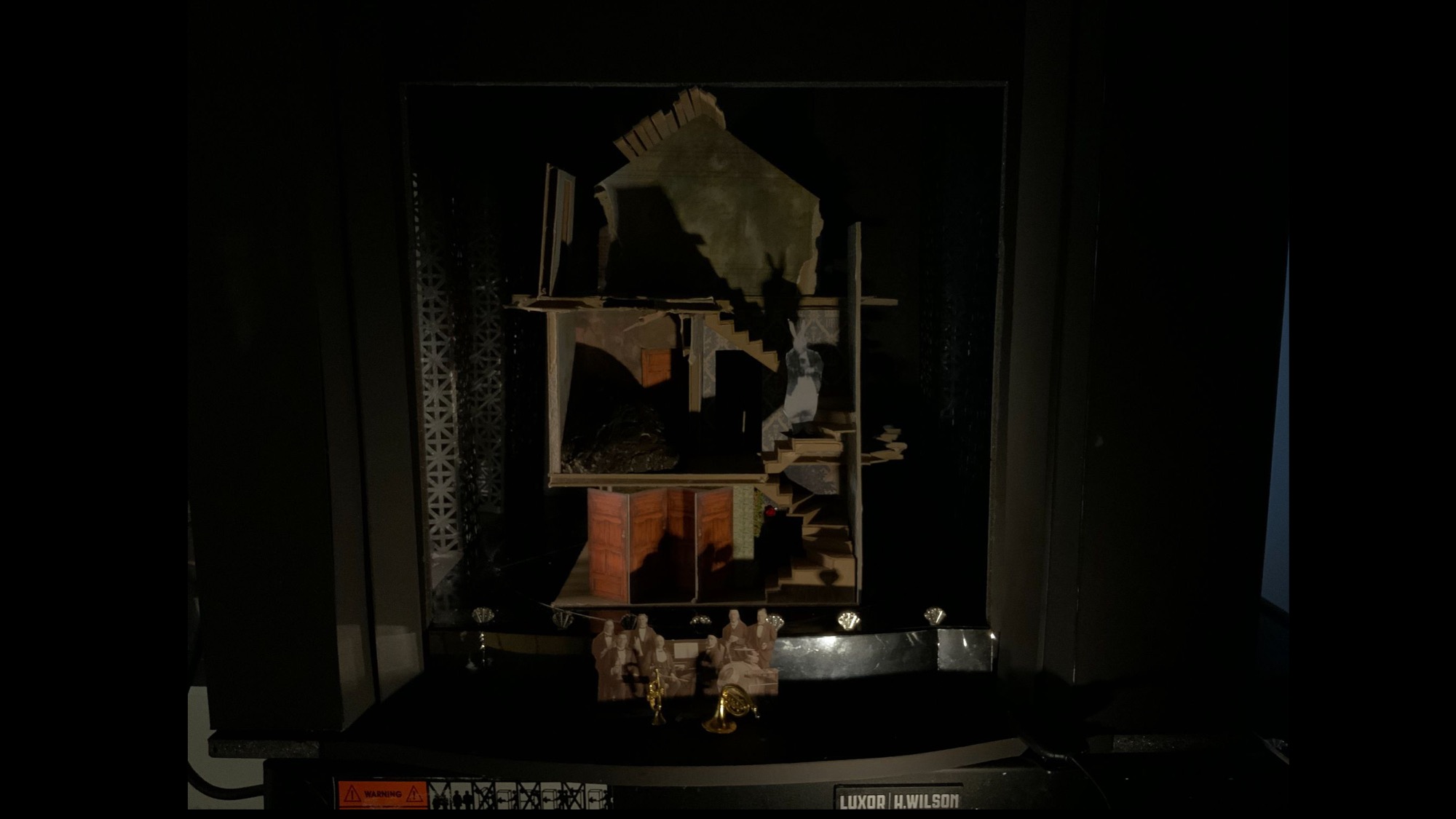

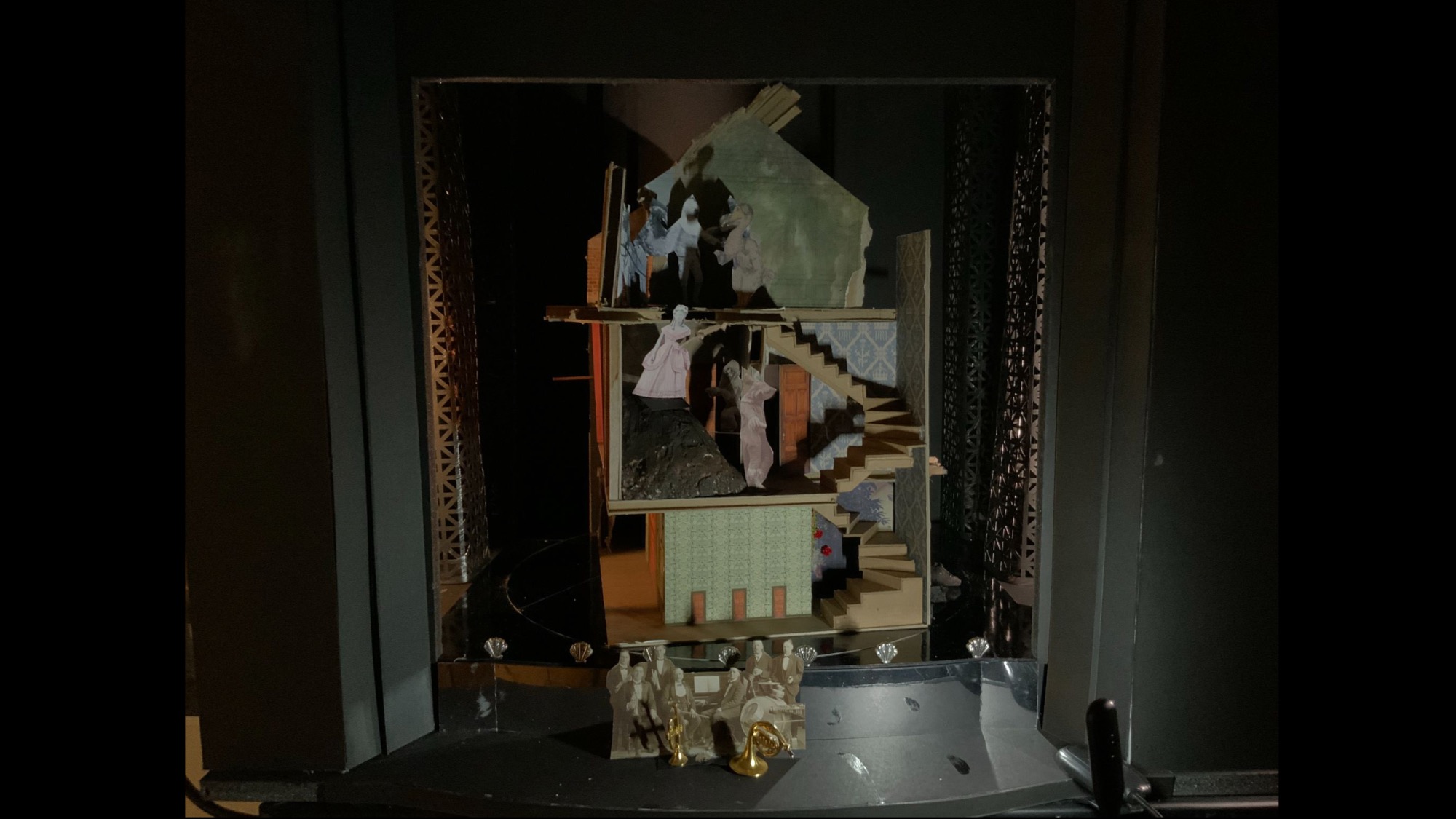

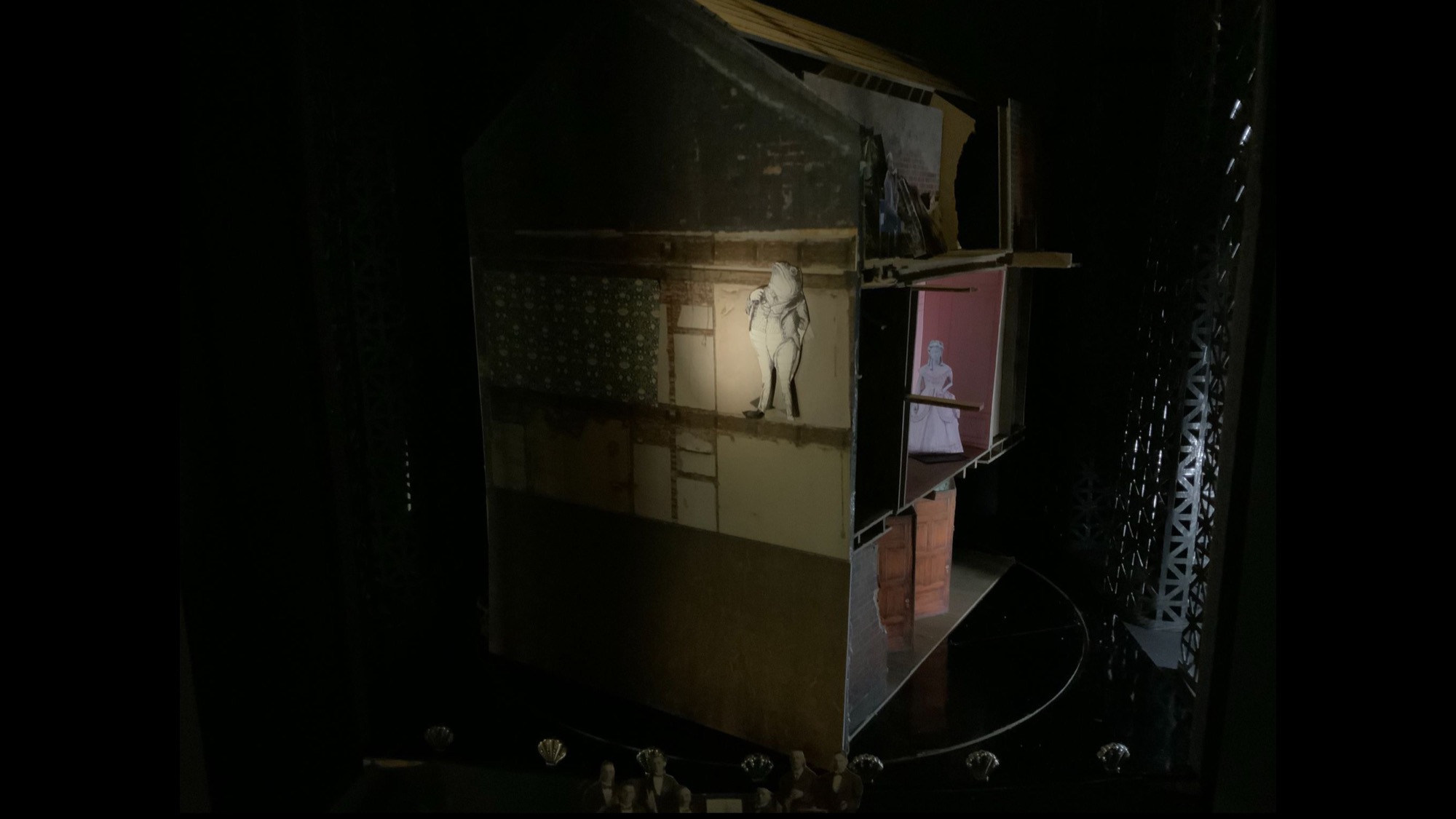

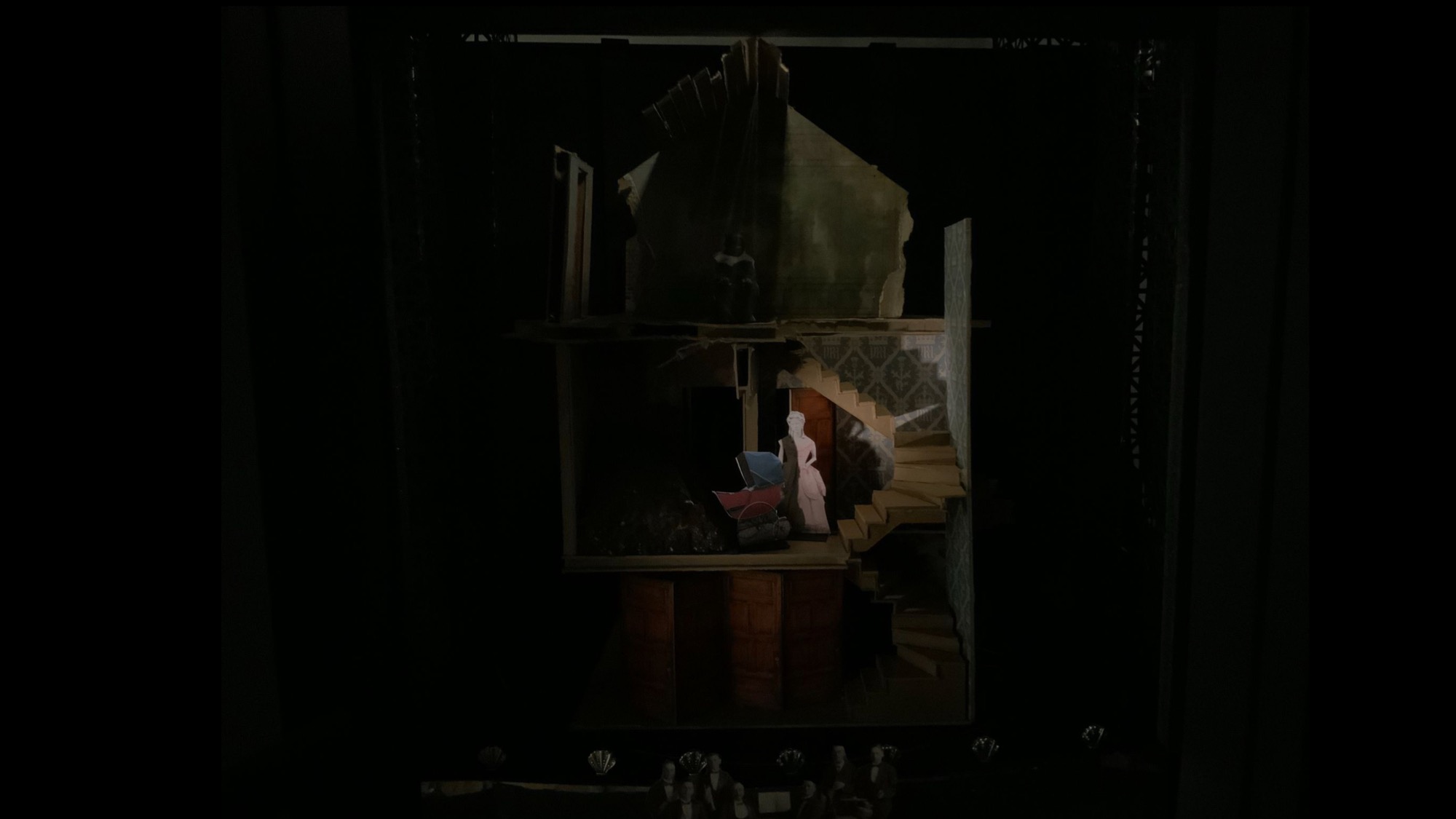

In this production of Unsuk Chin’s opera Alice in Wonderland (libretto by David Henry Hwang), responding to a particularly estranged and frightening tone and a vocabulary of lost authority in the libretto (over self, over others, over vassals, etc) the design seeks to frame the playful absurdity of the Alice’s narrative as a bitterly satirical and darker exploration of nonsensical behavior and loss of authority catalyzed by the end of the British empire. By adopting conventions of the uniquely English artform of pantomime theater, the production progresses roughly from the late 1800’s to the Blitz ending just after the 1997 handover of Hong Kong, the official end of the British Empire. When the audience enters, we see an asbestos painted fire curtain, a painted harpsichord being rummaged in and large scallop shell footlights. When the show starts, debris falls from the ceiling while Alice pleads with members of the orchestra to flee with her to safety, as well as actors planted in the audience.

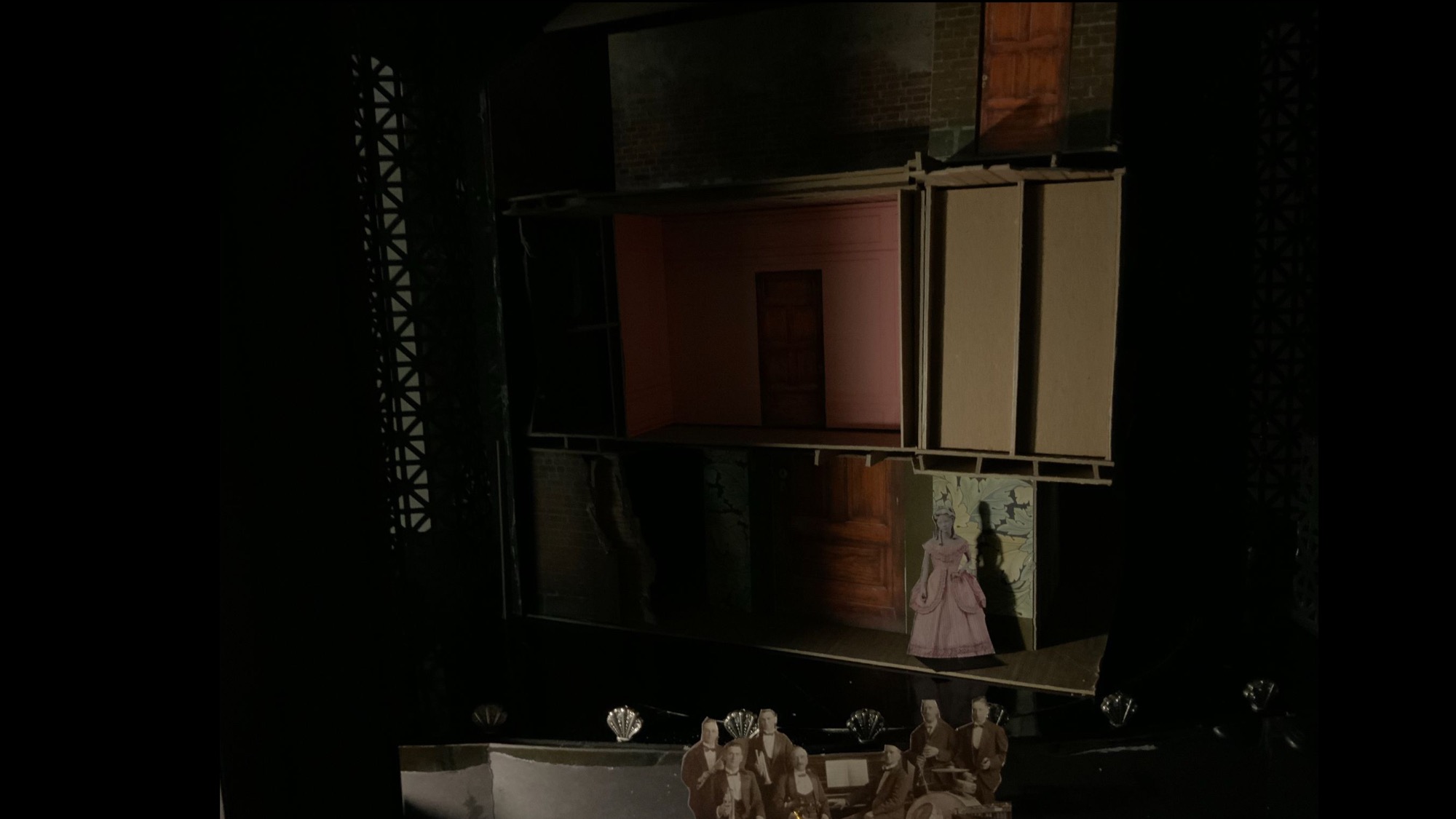

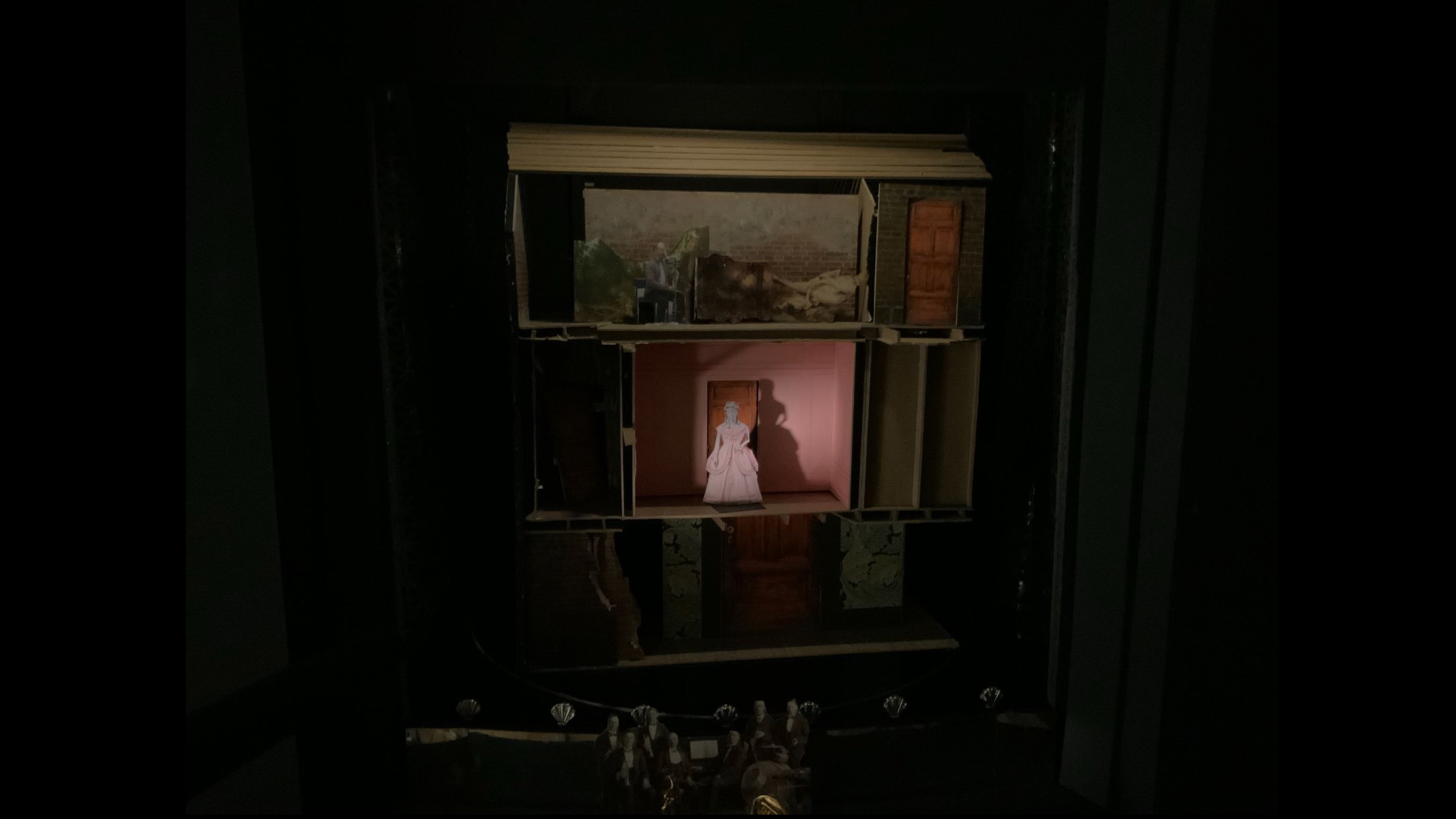

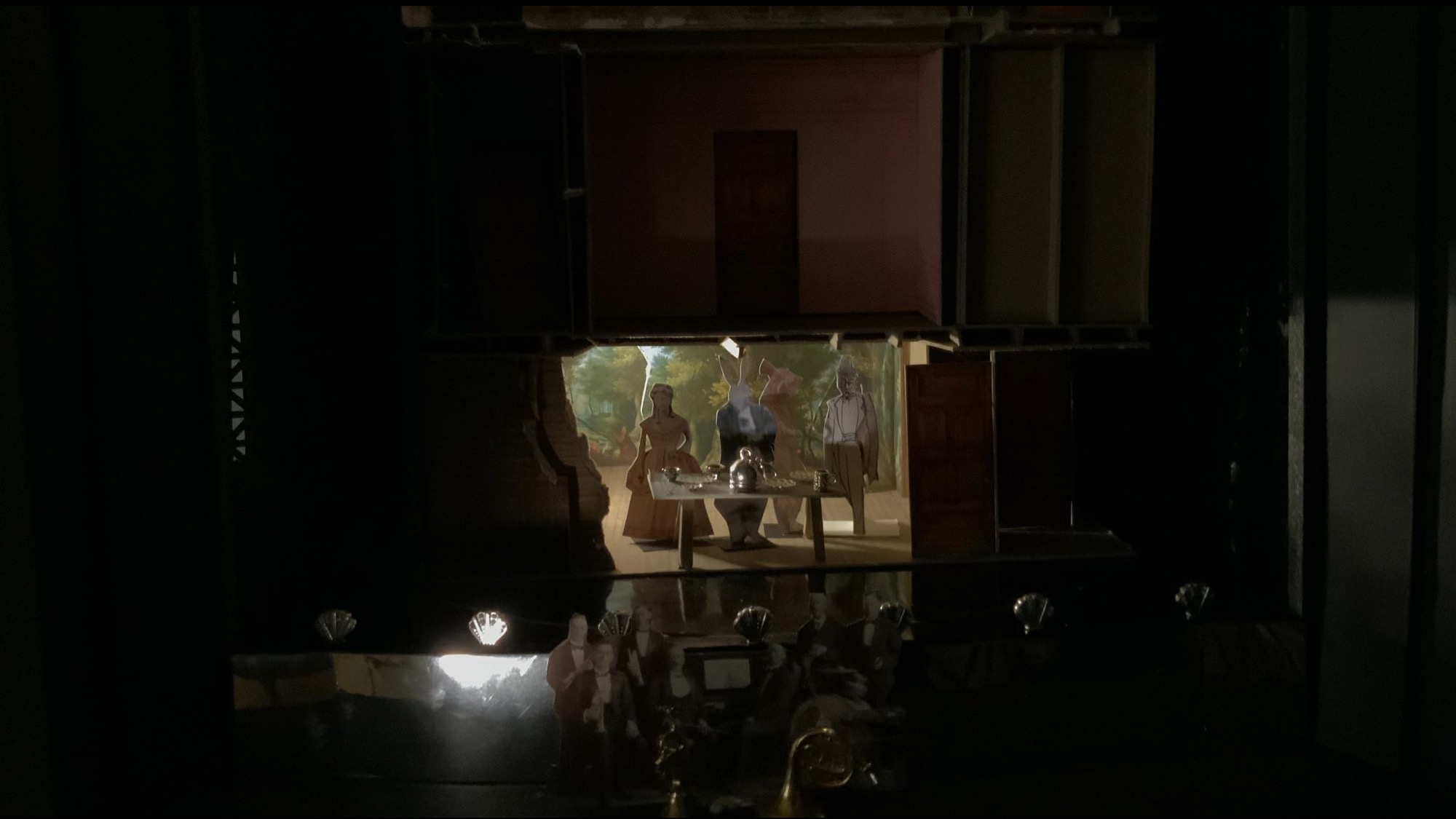

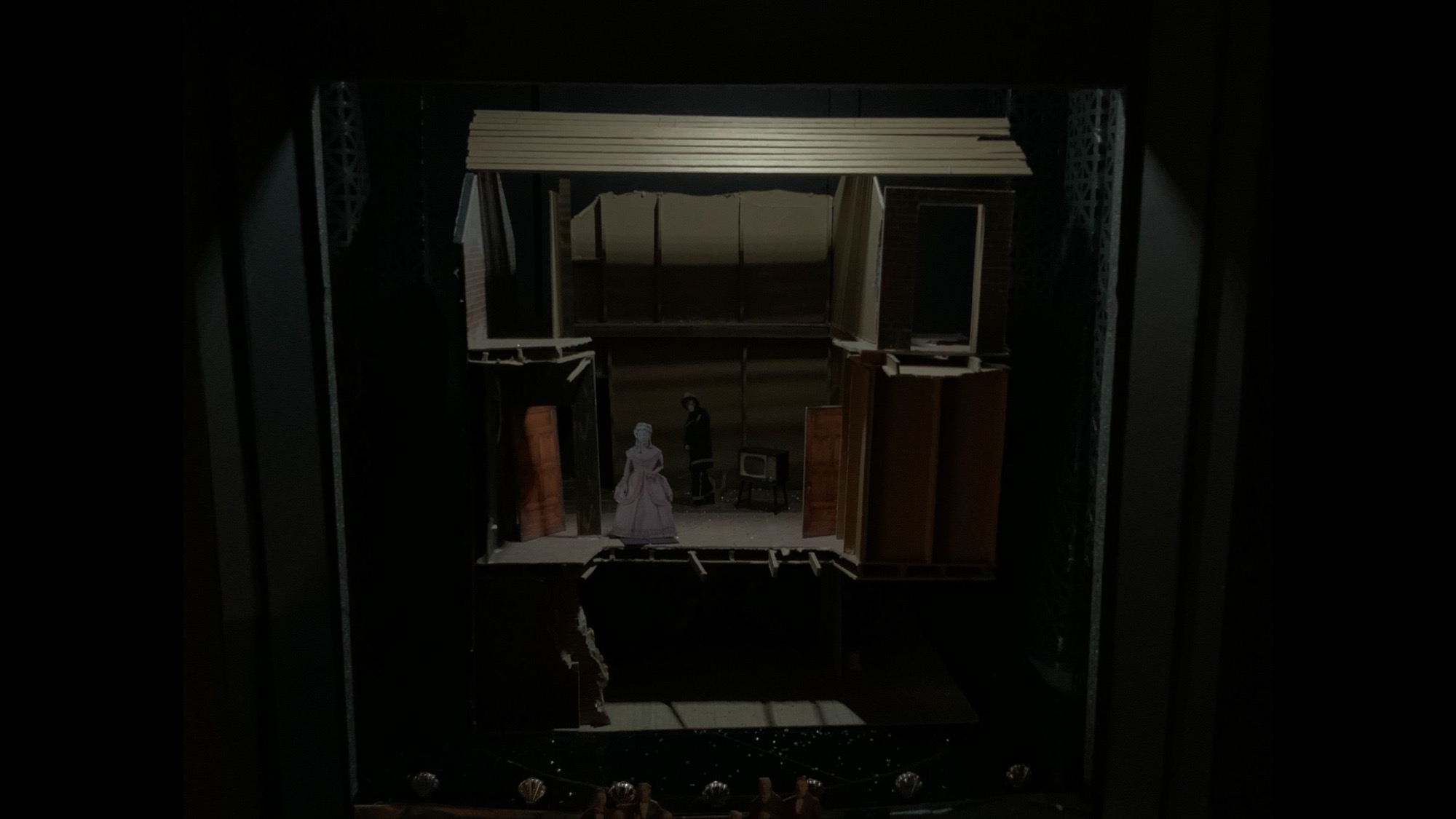

Alice is the pantomime treatment of the archetypal character, and initially, the ensemble is dressed in funny, strange English pantomime costumes. In the span of two hours, this is the last act of the British Empire, stretching roughly from the mid nineteenth century to the return of Hong Kong in 1997, the official end of the empire. In this version of the Alice in Wonderland set, the fall of the Empire is compressed into the space of a three-story home in order to spatialize the feeling of being stuck in a nation that is crumbling and unstable, the claustrophobia of the end of Empire. As the home turns, we see its destroyed exterior, the remnants of homes, a war-torn and neglected place and as it turns, rooms change and reveal different locations. The class structure of the empire is literalized between the floors, and that breaks down too as the house disintegrates more and more. Some rooms are paneled, some have Watteau paintings painted on the walls. Actor motivated folding screens of doors create endless hallways of only doors, hinging on themselves, leading nowhere. This, as we come to realize, is a distinctively British domestic structure but is many structures, many homes, and just beyond the threshold of the building, large metal towers rise on either side, resembling shipyards, “the ship of state.” The ensemble’s costumes begin to resemble, more and more, recognizable but uncanny human forms melded with animal symbolism.

As we continue through the piece, a room is removed by crane to reveal a forced perspective print of Windsor castle, with pews, and the Queen’s court envelops the whole home. Finally, in the last scene, red and silver confetti drops, and the space is transformed into a dimly top lit apartment just after the handover celebrations, with confetti and balloons on the floor, a thin dusting of confetti as the news plays on the TV. When the world erupts with colors, a prism of blinding colorful light and a huge, obscuring cloud of confetti fills the stage.

This harsh but fantastical final note: The final note of ambivalence reflects the ambivalence of the promise of end of empire: knowing both that empire still persists in many formations– political, social but often economic, but also the inherent hopefulness of freedom from the barren gardens caused by brutal Victorian empire-making.

MIMI LIEN’S SET DESIGN II at NYU TISCH

ALICE IN WONDERLAND

COMPOSED BY UNSUK CHIN

LIBRETTO BY DAVID HENRY-HWANG

THROUGH THE LENS OF THEATRICALITY, AN INSTRUMENTALIZATION OF THE FAMOUS FABLE TO TELL THE STORY OF A VIOLENT IMPERIAL POWER IN DECLINE

.

In this production of Unsuk Chin’s opera Alice in Wonderland (libretto by David Henry Hwang), responding to a particularly estranged and frightening tone and a vocabulary of lost authority in the libretto (over self, over others, over vassals, etc) the design seeks to frame the playful absurdity of the Alice’s narrative as a bitterly satirical and darker exploration of nonsensical behavior and loss of authority catalyzed by the end of the British empire. By adopting conventions of the uniquely English artform of pantomime theater, the production progresses roughly from the late 1800’s to the Blitz ending just after the 1997 handover of Hong Kong, the official end of the British Empire. When the audience enters, we see an asbestos painted fire curtain, a painted harpsichord being rummaged in and large scallop shell footlights. When the show starts, debris falls from the ceiling while Alice pleads with members of the orchestra to flee with her to safety, as well as actors planted in the audience.

Alice is the pantomime treatment of the archetypal character, and initially, the ensemble is dressed in funny, strange English pantomime costumes. In the span of two hours, this is the last act of the British Empire, stretching roughly from the mid nineteenth century to the return of Hong Kong in 1997, the official end of the empire. In this version of the Alice in Wonderland set, the fall of the Empire is compressed into the space of a three-story home in order to spatialize the feeling of being stuck in a nation that is crumbling and unstable, the claustrophobia of the end of Empire. As the home turns, we see its destroyed exterior, the remnants of homes, a war-torn and neglected place and as it turns, rooms change and reveal different locations. The class structure of the empire is literalized between the floors, and that breaks down too as the house disintegrates more and more. Some rooms are paneled, some have Watteau paintings painted on the walls. Actor motivated folding screens of doors create endless hallways of only doors, hinging on themselves, leading nowhere. This, as we come to realize, is a distinctively British domestic structure but is many structures, many homes, and just beyond the threshold of the building, large metal towers rise on either side, resembling shipyards, “the ship of state.” The ensemble’s costumes begin to resemble, more and more, recognizable but uncanny human forms melded with animal symbolism.

As we continue through the piece, a room is removed by crane to reveal a forced perspective print of Windsor castle, with pews, and the Queen’s court envelops the whole home. Finally, in the last scene, red and silver confetti drops, and the space is transformed into a dimly top lit apartment just after the handover celebrations, with confetti and balloons on the floor, a thin dusting of confetti as the news plays on the TV. When the world erupts with colors, a prism of blinding colorful light and a huge, obscuring cloud of confetti fills the stage.

This harsh but fantastical final note: The final note of ambivalence reflects the ambivalence of the promise of end of empire: knowing both that empire still persists in many formations– political, social but often economic, but also the inherent hopefulness of freedom from the barren gardens caused by brutal Victorian empire-making.

^ EMOTIONAL RESPONSE. OIL ON METAL PLATE.