MASTER’S THESIS for NYU TISCH

COMPOSED BY MARK-ANTHONY TURNAGE

LIBRETTO BY RICHARD THOMAS

VENUE: THE KOCH THEATER AT LINCOLN CENTER

Anna Nicole (2011) is an tragic opera with comic elements with music by Mark-Anthony Turnage and a libretto by Richard Thomas, celebrating the brief and tumultuous life of model, TV personality, and public figure Anna Nicole Smith: her escape from her humble beginnings in nowhere Texas, her entree into wealth through her marriage to an oil billionaire, her rise to Hollywood celebrity, and her subsequent struggles with addiction, and the death of herself and her son from overdose.

Initially I was attracted to the story because of my own biography: my childhood in Georgia was spent watching figures like Anna Nicole Smith on television or seeing her on tabloid covers. When I listened to the opera, I identified with her quest to get out of her small town and make herself into something larger and more magnified. In short, her hunger for fame is actually a desperate clawing for survival, for herself and her son, that ultimately goes awry. I identified with Anna Nicole as a figure celebrating working-class American Southerness, but moreover femininity, appetite, and shamelessness living in the extremity of bodily pleasure. However, Anna Nicole, her life and the opera, both end tragically; If Anna Nicole has a moral, it’s that the good life is probably one with some balance, and in a nation of extremity, when you are insatiable for life and its pleasure, it is very easy to lose that balance.

I also identified with the opera’s postmodern elements: the mixture of references to ‘high art’ and popular culture, and the characters’ own insistences and confessionals, their attempts to correct the past or revise it. The opera feeling mixes real shocking moments with dramatized ones. For me, this opera’s specific imagining of Anna Nicole’s story is to absorb the gravity of tragedy through the lens of American TV pop culture, musing on the nature of American culture, its endlessly self-replicating the reel of images that are reproduced over and over again, and its attendant psychic effects.

I wanted to avoid stereotypically bucolic or romantic representations of the American South, by using banal materials that speak to Anna Nicole’s humble beginnings but on a grand and extreme scale, instead portray this specific brand of capitalist American no-placeness. I wanted to use these materials to tell a story about confinement: the type imposed on us by the circumstances of our class/birth, the type that appears as freedom but slowly closes in around us, and the type we impose on ourselves. I wanted to portray affectively the feelings of these places on her, rather than just create a slideshow of biographical excerpts, the running theme of plywood specifically seeks to create an environment that is tonally warm and of the natural world, but in a commercialized and culturally neutered form.

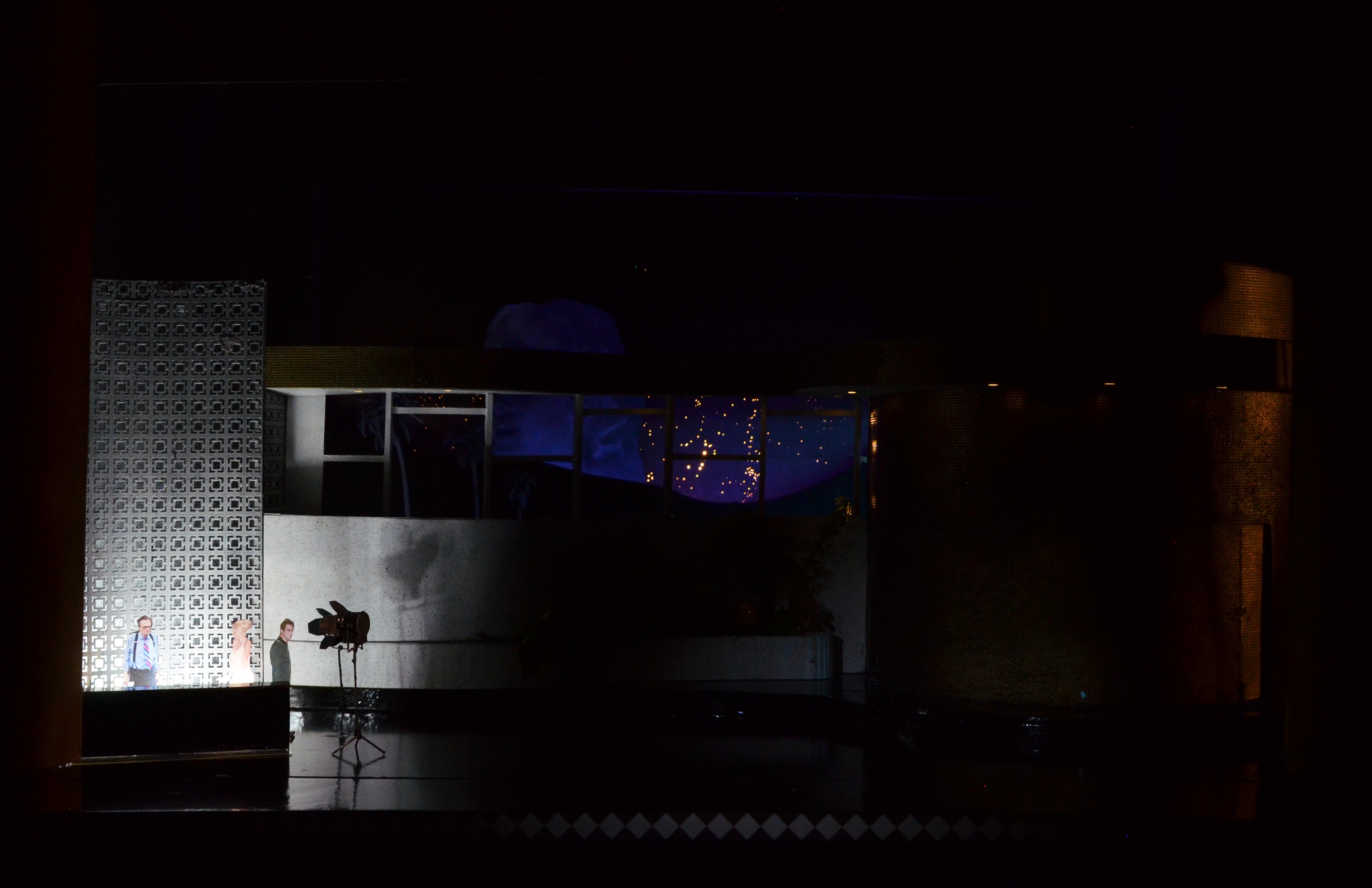

In Act 1, from the moment we enter the auditorium, we see a giant plywood wall pushed as far as feasibly possible against the front of the stage, lit severely and coldly by fluorescent light. It contains hidden entrances and exits that the other characters are able to traverse freely but Anna is not, and she’s instead trapped between us and the onstage audience. Anna Nicole self-directs, with a microphone in hand, a living tableaux tour of her childhood in Mexia on an elevated stage-within-a-stage, acted out by a mute, younger version of her in her blushing innocence. Mexia is represented by a shallow, painted faux wood backdrop; the lights begin to go from cold big box store lighting to gentle sunset tones. When she escapes Mexia only to find a different type of dead end in Houston, the painted backdrop goes away to reveal just another layer of plywood, vulgarly graffitied and marked up with branded signage, and the stage-within-a-stage construction breaks down, encompassing the whole space. The younger Anna Nicole disappears when she has her breast enhancement, and Anna goes from her presentation look into her coming out look: a strip club rendition of Marilyn’s nude dress. Anna’s entree into her fame is represented by a giant plywood wall printed with images of the real Anna Nicole Smith’s centerfolds and ads. The visual reprieve from the plywood room is her wedding, her achievement of some form of escape, and her exit is through a giant printed blue sky through an explosion of blue sky printed on plastic shimmering fringe curtain.

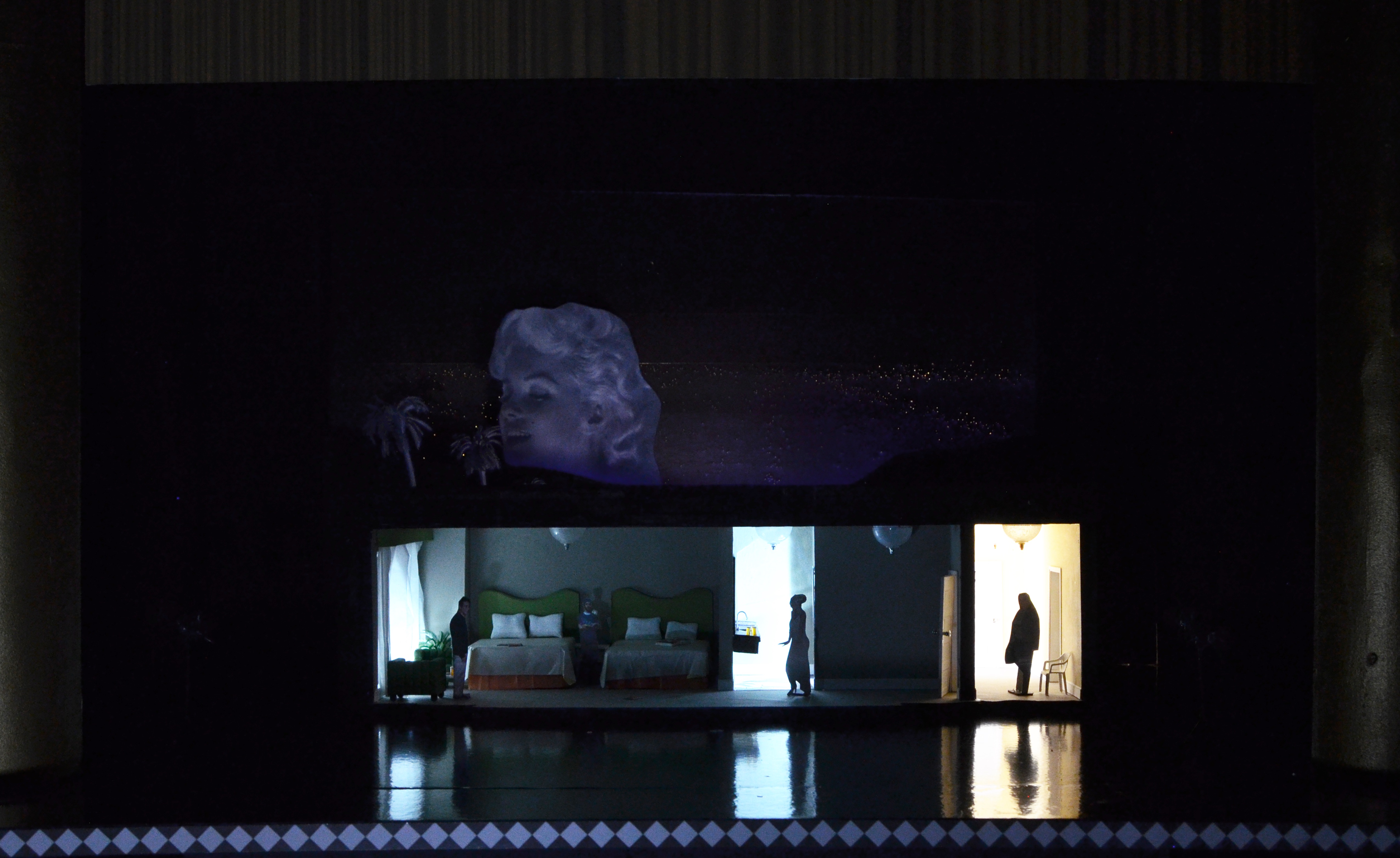

In Act 2, we’re transported to Anna's dream home in Los Angeles, featuring a giant gold mosaic tile drum riffing on the very American and decadent architectural language of Morris Lapidus, but still surrounded by banal materials like cinder block privacy bricks and a curved wall made of painted OSB. Images of Marilyn Monroe dominate her interior and the distant landscape, Anna Nicole’s personal Hollywood sign, hot pink and orange furniture, with stars dotting the light polluted landscape. Anna parties in a gold mesh dress that matches her house, while J. Howard wears a Hugh Hefner costume. When J. Howard Marshall goes into hospice and we jump ten years later, the stage pivots to create a constricted ground plan out of the same structure, the illusion of freedom and openness but still couched in her luxury. Anna’s costumes are more pieced together: her bustier on the Larry King show is strips of different fabric, her stole is made from her wedding furs.

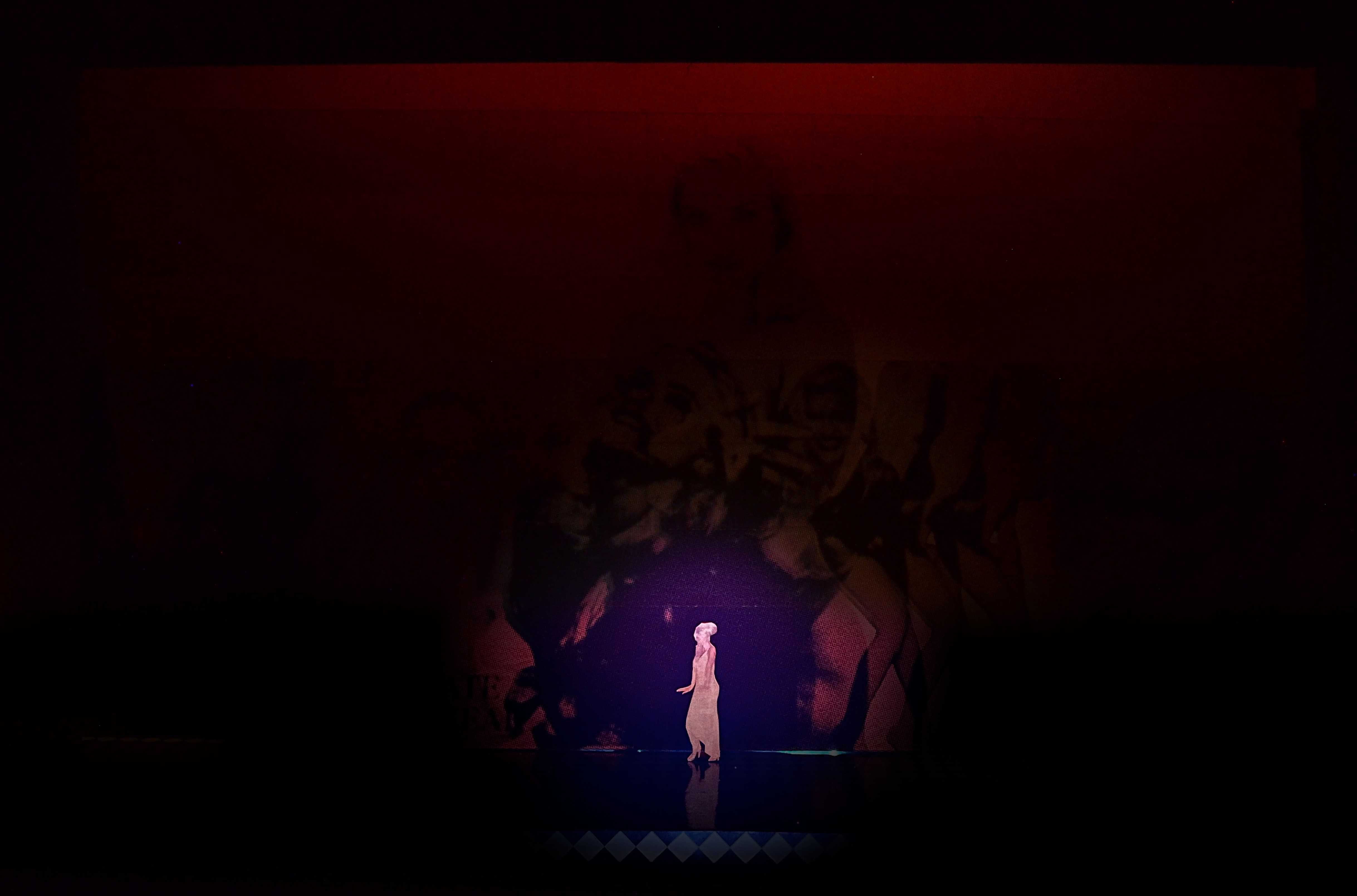

During the broadcast of Anna Nicole’s birth on TV, there’s a brief moment of joy, but then suddenly her fantasy ends as the opera takes a turn for the tragic. When the curtain rises on Act 3, we see a very small, lonely and desaturated hotel room, the plan and colors taken from the real hotel rooms at the Hard Rock Hotel where she actually overdosed. It’s surrounded by an inky void with details reminiscent of a soundstage. Her world has constricted even further in on her, and been drained of color. Anna wears her jewels from the previous acts but they’re constricting her, and she wears a real bathrobe from the Hard Rock Hotel. Faint colors of dawn begin to appear in the lighting, as Anna Nicole begins to apprehend her exploitation, to her son’s depression, to her birth and marriage. In the final moments, the hotel room slips away and we see the soundstage of her life: a crowd of figures from her life clapping underneath a flickering applause sign, fragments of her printed representations from Act 1, a ladder, and a giant red exit door. We see the groundrow we’ve been staring at the whole time is actually black painted, well-worn wood. Anna tells the audience she’d like to blow them a kiss one last time, and leaves the stage through the back: a gesture of release from herself, from us and our consumption of her.

ANNA NICOLE

COMPOSED BY MARK-ANTHONY TURNAGE

LIBRETTO BY RICHARD THOMAS

VENUE: THE KOCH THEATER AT LINCOLN CENTER

Anna Nicole (2011) is an tragic opera with comic elements with music by Mark-Anthony Turnage and a libretto by Richard Thomas, celebrating the brief and tumultuous life of model, TV personality, and public figure Anna Nicole Smith: her escape from her humble beginnings in nowhere Texas, her entree into wealth through her marriage to an oil billionaire, her rise to Hollywood celebrity, and her subsequent struggles with addiction, and the death of herself and her son from overdose.

Initially I was attracted to the story because of my own biography: my childhood in Georgia was spent watching figures like Anna Nicole Smith on television or seeing her on tabloid covers. When I listened to the opera, I identified with her quest to get out of her small town and make herself into something larger and more magnified. In short, her hunger for fame is actually a desperate clawing for survival, for herself and her son, that ultimately goes awry. I identified with Anna Nicole as a figure celebrating working-class American Southerness, but moreover femininity, appetite, and shamelessness living in the extremity of bodily pleasure. However, Anna Nicole, her life and the opera, both end tragically; If Anna Nicole has a moral, it’s that the good life is probably one with some balance, and in a nation of extremity, when you are insatiable for life and its pleasure, it is very easy to lose that balance.

I also identified with the opera’s postmodern elements: the mixture of references to ‘high art’ and popular culture, and the characters’ own insistences and confessionals, their attempts to correct the past or revise it. The opera feeling mixes real shocking moments with dramatized ones. For me, this opera’s specific imagining of Anna Nicole’s story is to absorb the gravity of tragedy through the lens of American TV pop culture, musing on the nature of American culture, its endlessly self-replicating the reel of images that are reproduced over and over again, and its attendant psychic effects.

I wanted to avoid stereotypically bucolic or romantic representations of the American South, by using banal materials that speak to Anna Nicole’s humble beginnings but on a grand and extreme scale, instead portray this specific brand of capitalist American no-placeness. I wanted to use these materials to tell a story about confinement: the type imposed on us by the circumstances of our class/birth, the type that appears as freedom but slowly closes in around us, and the type we impose on ourselves. I wanted to portray affectively the feelings of these places on her, rather than just create a slideshow of biographical excerpts, the running theme of plywood specifically seeks to create an environment that is tonally warm and of the natural world, but in a commercialized and culturally neutered form.

In Act 1, from the moment we enter the auditorium, we see a giant plywood wall pushed as far as feasibly possible against the front of the stage, lit severely and coldly by fluorescent light. It contains hidden entrances and exits that the other characters are able to traverse freely but Anna is not, and she’s instead trapped between us and the onstage audience. Anna Nicole self-directs, with a microphone in hand, a living tableaux tour of her childhood in Mexia on an elevated stage-within-a-stage, acted out by a mute, younger version of her in her blushing innocence. Mexia is represented by a shallow, painted faux wood backdrop; the lights begin to go from cold big box store lighting to gentle sunset tones. When she escapes Mexia only to find a different type of dead end in Houston, the painted backdrop goes away to reveal just another layer of plywood, vulgarly graffitied and marked up with branded signage, and the stage-within-a-stage construction breaks down, encompassing the whole space. The younger Anna Nicole disappears when she has her breast enhancement, and Anna goes from her presentation look into her coming out look: a strip club rendition of Marilyn’s nude dress. Anna’s entree into her fame is represented by a giant plywood wall printed with images of the real Anna Nicole Smith’s centerfolds and ads. The visual reprieve from the plywood room is her wedding, her achievement of some form of escape, and her exit is through a giant printed blue sky through an explosion of blue sky printed on plastic shimmering fringe curtain.

In Act 2, we’re transported to Anna's dream home in Los Angeles, featuring a giant gold mosaic tile drum riffing on the very American and decadent architectural language of Morris Lapidus, but still surrounded by banal materials like cinder block privacy bricks and a curved wall made of painted OSB. Images of Marilyn Monroe dominate her interior and the distant landscape, Anna Nicole’s personal Hollywood sign, hot pink and orange furniture, with stars dotting the light polluted landscape. Anna parties in a gold mesh dress that matches her house, while J. Howard wears a Hugh Hefner costume. When J. Howard Marshall goes into hospice and we jump ten years later, the stage pivots to create a constricted ground plan out of the same structure, the illusion of freedom and openness but still couched in her luxury. Anna’s costumes are more pieced together: her bustier on the Larry King show is strips of different fabric, her stole is made from her wedding furs.

During the broadcast of Anna Nicole’s birth on TV, there’s a brief moment of joy, but then suddenly her fantasy ends as the opera takes a turn for the tragic. When the curtain rises on Act 3, we see a very small, lonely and desaturated hotel room, the plan and colors taken from the real hotel rooms at the Hard Rock Hotel where she actually overdosed. It’s surrounded by an inky void with details reminiscent of a soundstage. Her world has constricted even further in on her, and been drained of color. Anna wears her jewels from the previous acts but they’re constricting her, and she wears a real bathrobe from the Hard Rock Hotel. Faint colors of dawn begin to appear in the lighting, as Anna Nicole begins to apprehend her exploitation, to her son’s depression, to her birth and marriage. In the final moments, the hotel room slips away and we see the soundstage of her life: a crowd of figures from her life clapping underneath a flickering applause sign, fragments of her printed representations from Act 1, a ladder, and a giant red exit door. We see the groundrow we’ve been staring at the whole time is actually black painted, well-worn wood. Anna tells the audience she’d like to blow them a kiss one last time, and leaves the stage through the back: a gesture of release from herself, from us and our consumption of her.

^PRE-SHOW

^ACT ONE OPENING. CHORUS: “THERE ONCE WAS A LADY / WHO WANTED TO BE MARILYN MORNOE.”

ANNA APPEARS. ANNA: “I WANT TO BLOW YOU ALL / BLOW YOU ALL A KISS!”

ANNA APPEARS. ANNA: “I WANT TO BLOW YOU ALL / BLOW YOU ALL A KISS!” ANNA REVEALS MEXIA AND YOUNG ANNA NICOLE. “MEXIA WEREN’T NO PLACE TO LIVE / IT WAS A PLACE WHERE YOUR BODY ONLY KINDA FUNCTIONED.”

ANNA REVEALS MEXIA AND YOUNG ANNA NICOLE. “MEXIA WEREN’T NO PLACE TO LIVE / IT WAS A PLACE WHERE YOUR BODY ONLY KINDA FUNCTIONED.”  JIM’S KRISPY FRIED CHICKEN / DANIEL’S ENTRANCE

JIM’S KRISPY FRIED CHICKEN / DANIEL’S ENTRANCE TRANSITION TO HOUSTON / THE STRIP CLUB. “WE ARE LAP DANCERS / WE DANCE IN LAPS.”

TRANSITION TO HOUSTON / THE STRIP CLUB. “WE ARE LAP DANCERS / WE DANCE IN LAPS.”  DR. YES’ PLASTIC SURGERY: “GET REAL / GET SURGERY / OR GO BACK TO POVERTY”

DR. YES’ PLASTIC SURGERY: “GET REAL / GET SURGERY / OR GO BACK TO POVERTY” ANNA’S BODY TRANSFORMATION/DEBUT: “ALL YOU NEED IS DREAMS.”

ANNA’S BODY TRANSFORMATION/DEBUT: “ALL YOU NEED IS DREAMS.”

J. HOWARD MARSHALL’S ENTRANCE: “I AM J. HOWARD MARSHALL ... I AM THE AMERICAN DREAM.”

J. HOWARD MARSHALL’S ENTRANCE: “I AM J. HOWARD MARSHALL ... I AM THE AMERICAN DREAM.” “DANIEL ... WE GOT THE RANCH.”

“DANIEL ... WE GOT THE RANCH.” ANNA: “AMERICAN DREAM, AMERICAN DREAM ... I’M GONNA CRACK IT OPEN / AND LAP UP THE CREAM.”

ANNA: “AMERICAN DREAM, AMERICAN DREAM ... I’M GONNA CRACK IT OPEN / AND LAP UP THE CREAM.”  ANNA AND J. HOWARD WEDDING: “EASE THE PAIN / BLOCK THE SHAME / DOWN THE HATCH” “GO ANNA, YOU GO GIRL!”

ANNA AND J. HOWARD WEDDING: “EASE THE PAIN / BLOCK THE SHAME / DOWN THE HATCH” “GO ANNA, YOU GO GIRL!”

^INTERMISSION

^ACT TWO “DO YOU HEAR THAT SOUND? ... JIMMY CHOO SHOES ON THE RED CARPET...”

ANNA: “ALRIGHT! TIME TO PARTY!”

ANNA: “ALRIGHT! TIME TO PARTY!”

VIRGIE AND DANIEL APPEARS. VIRGIE: “I SCHOOLED HIM, I FED HIM, I LOVED HIM... MOTHERS, YOU’RE ALWAYS LEFT HOLDING THE BABY!”

VIRGIE AND DANIEL APPEARS. VIRGIE: “I SCHOOLED HIM, I FED HIM, I LOVED HIM... MOTHERS, YOU’RE ALWAYS LEFT HOLDING THE BABY!” J. HOWARD MARSHALL HOSPICE AND MARHSALL FAMILY APPEARS. MARSHALL: ANNA, YOU WERE MY SPRING. FAMILY: SHE WAS YOUR WINTER WHEN THE BILLS ROLLED IN.

J. HOWARD MARSHALL HOSPICE AND MARHSALL FAMILY APPEARS. MARSHALL: ANNA, YOU WERE MY SPRING. FAMILY: SHE WAS YOUR WINTER WHEN THE BILLS ROLLED IN.

^10 YEARS LATER TRANSITION. ALL THE DIFFERENT SILHOUETTES OF ANNA NICOLE RUN ACROSS WHILE THE STAGE IS CLEARED AND THE GROUNDPLAN GETS SHALLOWER.

BACKSTAGE AT THE LARRY KING. ANNA: “I’M ANNA NICOLE AND I VOMIT ON DOLLY PARTON’S SHOES!”

BACKSTAGE AT THE LARRY KING. ANNA: “I’M ANNA NICOLE AND I VOMIT ON DOLLY PARTON’S SHOES!” LARRY KING, ON AIR. ANNA: “IT’S ALL ABOUT DREAMS! AND MORE IMPORTANTLY, DOGS!”

LARRY KING, ON AIR. ANNA: “IT’S ALL ABOUT DREAMS! AND MORE IMPORTANTLY, DOGS!” HOWARD K. STERN ARIA: “WE NEED MORE MONEYSHOTS.”

HOWARD K. STERN ARIA: “WE NEED MORE MONEYSHOTS.” BIRTHING SCENE. ANNA: “I CAN’T FEEL NO PAIN.” HOWARD (OFFSTAGE): “YOU’RE GETTING A MILLION / ACT / ACT LIKE THERE’S SOME PAIN.”

BIRTHING SCENE. ANNA: “I CAN’T FEEL NO PAIN.” HOWARD (OFFSTAGE): “YOU’RE GETTING A MILLION / ACT / ACT LIKE THERE’S SOME PAIN.”

^ACT THREE ANNA: “FOR A WHILE THERE, WE HAD IT ALL GOIN. DIDN’T WE?” THE HARD ROCK HOTEL ROOM SET APPEARS.

DANIEL’S OVERDOSE / DRUG BALLAD SLOW DANCE.

DANIEL’S OVERDOSE / DRUG BALLAD SLOW DANCE.  ANNA’S OVERDOSE: “DANIEL’S WAITING FOR ME ON THE OTHER SIDE.”

ANNA’S OVERDOSE: “DANIEL’S WAITING FOR ME ON THE OTHER SIDE.”

FINALE. ANNA: “I MADE SOME BAD CHOICE. MADE SOME WORSE CHOICES. THEN RAN OUT OF CHOICES.” ANNA AND YOUNG ANNA EXIT OUT THE BACK.