UNREALIZED SCENIC DESIGN for MIMI LIEN’S SET DESIGN II course at NYU TISCH

WRITTEN BY TARRELL ALVIN MCCRANEY

AN EXTENSION OF MCCRANEY’S MINGLING OF THE MUNDANE AND THE HOLY, TO EXPLORE HOW MAPS ARE EMBLEMATIC OF POLITICAL POWER AND DIASPORIC REALITIES AND ALSO TO EXPLORE THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HIGH TRAGEDY AND DEPRESSION.

In this production of McCraney’s In The Red and Brown Water, we learn the story of Oya, and by extension, her community in San Pere, Louisiana. Drawing from the materials of CJ Peete, panorama paintings, prehistoric map carvings, Southern porches, the scenery is highly influenced by the role of ritual drama: McCraney’s idiosyncratic mix of Greek tragedy, Yoruban Odu, and a more local domestic drama about the relationships within a pre-Katrina community. In this genre, he is telling the story of Oya, primarily, and, It is through the exploration of Oya’s character (who is many things, but both a human figure on a human scale and with quotidian conflicts as well as a deity who is inextricably linked with the elements) and her harmatia, that we actually explore a civic reality within this particular community. As the secondary readings point out, she threatens their main values of family, family production, and community bonds with her self destruction. Her connection to the wind and water threatens the literal destruction of this community on a more ecological cosmic level. Most important, she is a woman struggling with depression who finds no other way to live and resorts to self-violence to cope with heartbreak, loss of identity, an inability to relate to people who love and include her in their lives.

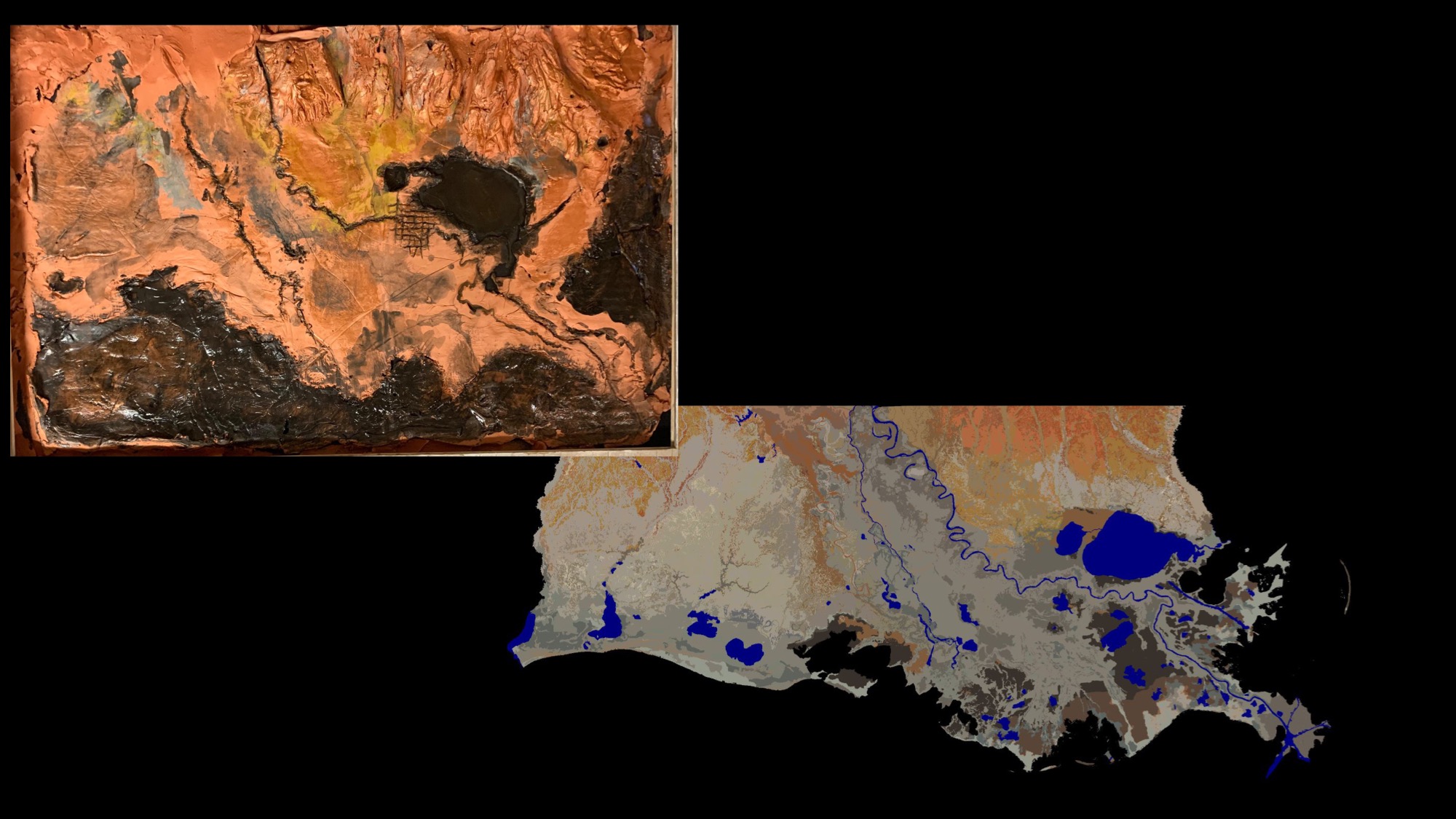

The sense of community, and its relationship to the world, is grounded in the platea they’ve been given to perform upon: a clay panoramic view of the world. They move across its stained surface with respect. In thinking of maps, I’ve thought deeply about how maps can come to symbolize a cruel, abstracted and subjugative view of the world, and sought to find a more localized, sculptural language (made from an approximation of Lousianna colonial era building techniques, in contrast to the brick masonry of the workshop which evokes images of the Bricks in pre-Kartina housing projects, specifically CJ Peete) that illustrated a relationship to place, a cohabitation of place and making that literally sets the stage for the drama to commence.

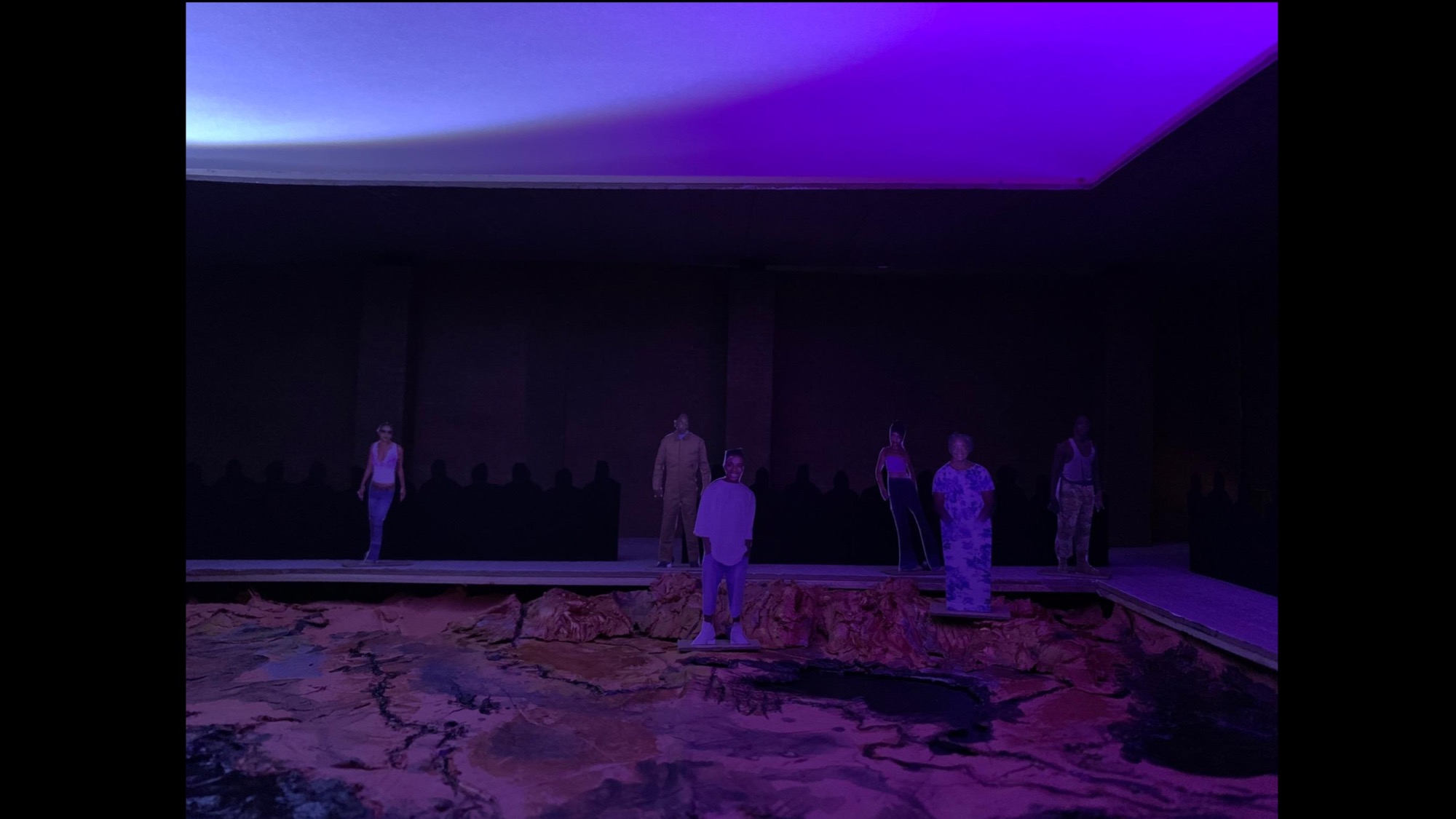

The space is a raised platform with ladderback chairs surrounding an 18” pit filled with earth. The floor and ceiling are white stained planks, creaking as you walk, that you might find on an old porch. We have a sense this is a meeting place, an extemporaneous performance site, more than a theater. The earth is clay, mixed with spanish moss and formed and incised into a landscape topographic map of the surrounding area. It extends under the seats, and features indentations were the rivers and the coast mingle with the gulf. When actors are not in a scene, they are actively watching, sitting along the edge of the pit. They are both themselves and themselves playing a character, many realities existing at once.

Above is a representation of the sky, where soft interplays of ambient light are the only light to the scene, once again magnifying the actors to appear between heaven and the earth. The sky also represents divine inspiration in a way, echoing the structure of the orisha’s devotion to Orunmilia. The sky also echoes the passage of language in the play from “Oya looks to the sky for answers” to “Oya looks at the ceiling” and at the end, the luminous source of light is a dead, gray patch of ceiling, and everyone is lit from the side.

IN THE RED AND BROWN WATER

WRITTEN BY TARRELL ALVIN MCCRANEY

AN EXTENSION OF MCCRANEY’S MINGLING OF THE MUNDANE AND THE HOLY, TO EXPLORE HOW MAPS ARE EMBLEMATIC OF POLITICAL POWER AND DIASPORIC REALITIES AND ALSO TO EXPLORE THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HIGH TRAGEDY AND DEPRESSION.

In this production of McCraney’s In The Red and Brown Water, we learn the story of Oya, and by extension, her community in San Pere, Louisiana. Drawing from the materials of CJ Peete, panorama paintings, prehistoric map carvings, Southern porches, the scenery is highly influenced by the role of ritual drama: McCraney’s idiosyncratic mix of Greek tragedy, Yoruban Odu, and a more local domestic drama about the relationships within a pre-Katrina community. In this genre, he is telling the story of Oya, primarily, and, It is through the exploration of Oya’s character (who is many things, but both a human figure on a human scale and with quotidian conflicts as well as a deity who is inextricably linked with the elements) and her harmatia, that we actually explore a civic reality within this particular community. As the secondary readings point out, she threatens their main values of family, family production, and community bonds with her self destruction. Her connection to the wind and water threatens the literal destruction of this community on a more ecological cosmic level. Most important, she is a woman struggling with depression who finds no other way to live and resorts to self-violence to cope with heartbreak, loss of identity, an inability to relate to people who love and include her in their lives.

The sense of community, and its relationship to the world, is grounded in the platea they’ve been given to perform upon: a clay panoramic view of the world. They move across its stained surface with respect. In thinking of maps, I’ve thought deeply about how maps can come to symbolize a cruel, abstracted and subjugative view of the world, and sought to find a more localized, sculptural language (made from an approximation of Lousianna colonial era building techniques, in contrast to the brick masonry of the workshop which evokes images of the Bricks in pre-Kartina housing projects, specifically CJ Peete) that illustrated a relationship to place, a cohabitation of place and making that literally sets the stage for the drama to commence.

The space is a raised platform with ladderback chairs surrounding an 18” pit filled with earth. The floor and ceiling are white stained planks, creaking as you walk, that you might find on an old porch. We have a sense this is a meeting place, an extemporaneous performance site, more than a theater. The earth is clay, mixed with spanish moss and formed and incised into a landscape topographic map of the surrounding area. It extends under the seats, and features indentations were the rivers and the coast mingle with the gulf. When actors are not in a scene, they are actively watching, sitting along the edge of the pit. They are both themselves and themselves playing a character, many realities existing at once.

Above is a representation of the sky, where soft interplays of ambient light are the only light to the scene, once again magnifying the actors to appear between heaven and the earth. The sky also represents divine inspiration in a way, echoing the structure of the orisha’s devotion to Orunmilia. The sky also echoes the passage of language in the play from “Oya looks to the sky for answers” to “Oya looks at the ceiling” and at the end, the luminous source of light is a dead, gray patch of ceiling, and everyone is lit from the side.